How To Get Started Writing Children's Books

As a children's book editor, I've helped hundreds of authors write, edit and publish their children's book.

As a children's book editor, I've helped hundreds of authors write, edit and publish their children's book.

Anyone can sit down and dash out a children's book, and with a little help and guidance, yours can be good enough to earn the attention of thousands of children.

And nothing beats the feeling of holding your printed book in your hands and reading it to a child for the first time. Follow these 12 steps and you'll get there in no time.

In this article you'll learn:

- How to generate a concept that works

- How to create a main character that children love

- How to write the right length

- How to structure the plot

- How to work with an illustrator

- How to revise

- How to publish

Lastly, you can read this whole post and get a decent understanding of how to write a children's book, but if you want the full, in-depth experience with even more information, videos, PDFs, quizzes, and exercises, you can take my 30-video course on how to write a children's book called, "Two Weeks To Your Best Children's Book."

Here is the first video that tells you about contents of the course:

And if you just have a few questions about what to do with your children's book, skip to the end and read the commonly asked questions. I probably address what you're wondering about, and if not, leave a comment and I'll answer it!

Okay, buckle up and get ready! These are the 12 steps to writing a children's book.

1. Find Your Best Idea

1. Find Your Best Idea

You probably have an idea already, but you should work on refining it. Here's how:

- Google "children's book" and a phrase that describes your book.

- Once you've found books that are similar, look at the summary of those books.

- Figure out how your book is different than the published ones.

This might seem commonsense to check what's already out there before putting all your time and energy into a book, but so many authors don't do it! This is just basic research that you can do in 2 minutes that will give you a sense of competing books.

When I lead most authors through this process, they discover that their idea has already been written about. Now, that's not necessarily a bad thing — actually, it's proof that children want to read about their topic!

When I lead most authors through this process, they discover that their idea has already been written about. Now, that's not necessarily a bad thing — actually, it's proof that children want to read about their topic!

The trick is to have one twist for your story that makes it different. If it's a story about bullying, perhaps your book tells the story from the point of view of the bully! Or if it's a story about a dog, make this dog a stray or blind in one eye.

Want more ideas for children's book? Check out these 9 quirky and zany ideas.

Maybe your story is different because you have a surprise at the end, or maybe it's different because it's for an older or younger age group, or your character has a magical guide like a fairy or elf to lead them through their journey. Just add one twist that distinguishes it from other books.

2. Develop Your Main Character

2. Develop Your Main Character

I edit hundreds of children's books every year, and the best books have unique characters. They are quirky in some way. They have a funny habit. They look strange. They talk differently than everyone else.

But when I see a book where the main character is indistinguishable from every child, that worries me. You don't want a character who stands in for every child, you want a main character that feels REAL.

My advice would be to go through a Character Questionnaire and figure out how much you know about your character:

- What does your main character desire?

- What is their best/worst habit?

- Are they an extrovert or introvert?

- How do they speak differently than everyone else? (cute sayings, repeated phrase/word, dialect, high/low volume)

- Do they doubt themselves or do they have too much bravery?

- Do they have any pets? (or does your animal character have human owners)

- What makes your main character feel happy?

- Do they have any secrets?

- What would this character do that would be very out of character?

- What is one thing this character loves that most people dislike?

Now score yourself on how many you knew right away:

8 – 10

8 – 10

I give you a thousand gold ribbons. Your character probably feels like a real person to you.

6 – 7

6 – 7

Great job! You have thought deeply about your character.

5 and below

5 and below

Take a few more character questionnaires before you start writing.

If you'd like more questions, I have an expanded version of this questionnaire in my course.

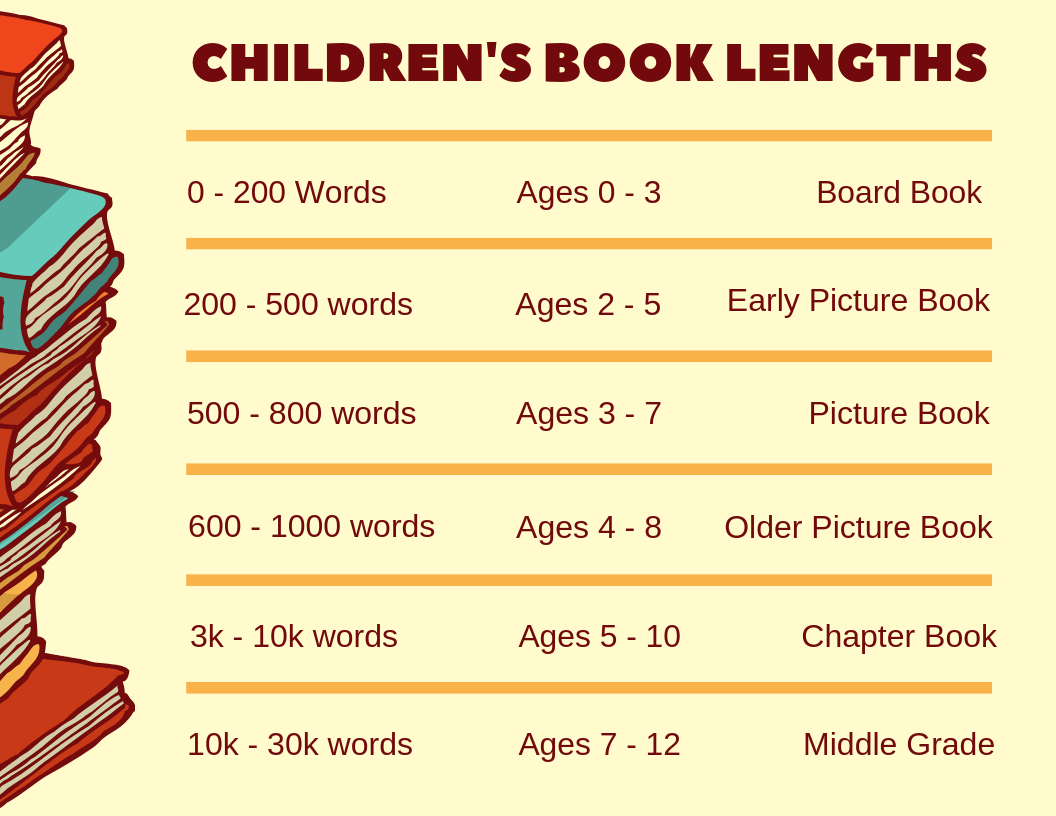

3. Write the Right Length

What's the right word count for your book?

This is probably the most common question I get asked, and it's also the one that most writers get wrong.

Ultimately, you need to figure out what age range you're writing for, and then write within that word count.

Most writers are writing picture books for ages 3 – 7 — that's the most common category. If that's you, then shoot for 750 words. That's the sweet spot.

Most writers are writing picture books for ages 3 – 7 — that's the most common category. If that's you, then shoot for 750 words. That's the sweet spot.

If you write a picture book more than 1,000 words, you're sunk. You absolutely have to keep it under 1,000 words. It's the most unyielding rule in the entire industry. Seriously, take out all the red pens and slash away until you've whittled it down.

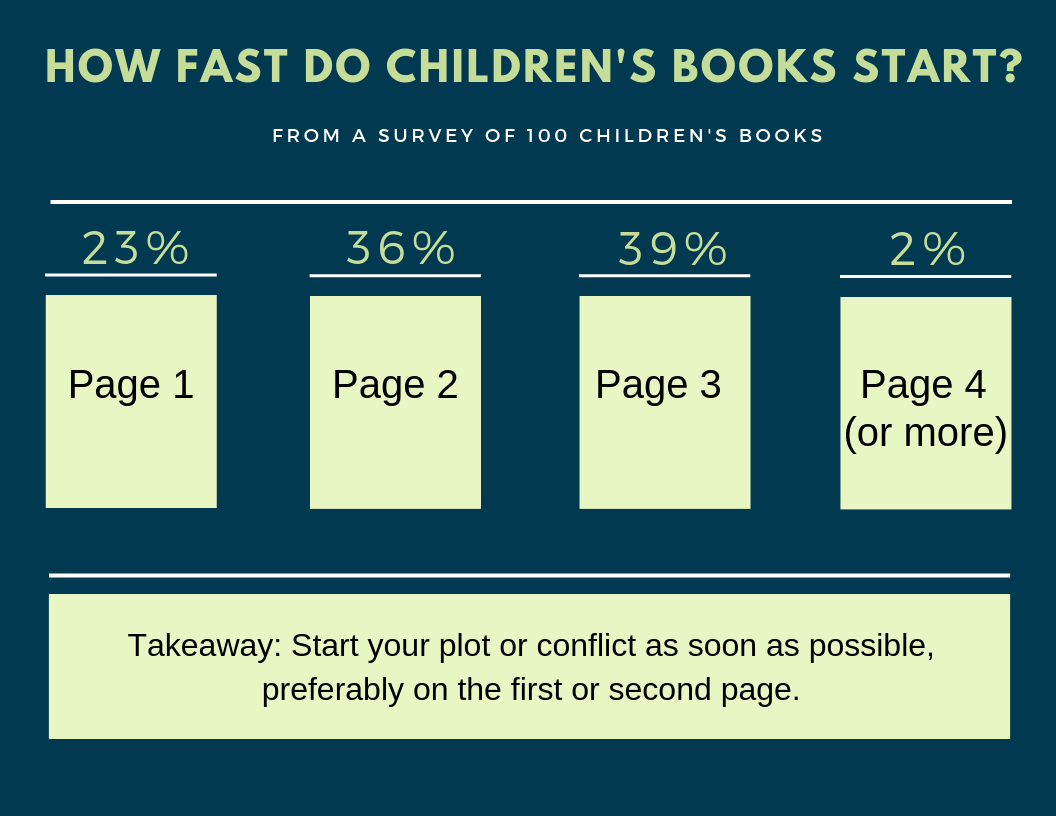

4. Start the Story Quickly

Many unpublished children's books fail to grab the child's attention (and parent's attention!), and that's because they start too slow. If your story is about a child joining a circus, they should join on the first or second page.

Don't give backstory about this child's life. Don't set the scene or tell us what season it is.

Just have the circus come into town, and as soon as possible, have the child become a clown or tightrope walker or lion tamer.

You have such a short space to tell your story that you can't waste any time. The pacing of children's stories generally moves lickety-split, so don't write at a tortoise pace.

You have such a short space to tell your story that you can't waste any time. The pacing of children's stories generally moves lickety-split, so don't write at a tortoise pace.

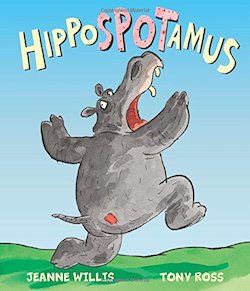

For instance, look at the picture book "HippoSPOTamus." When do you think the hippo discovers the red spot on her bottom?

Yep, it's on the first page.

And that event launches the entire story.

Start your book that quickly.

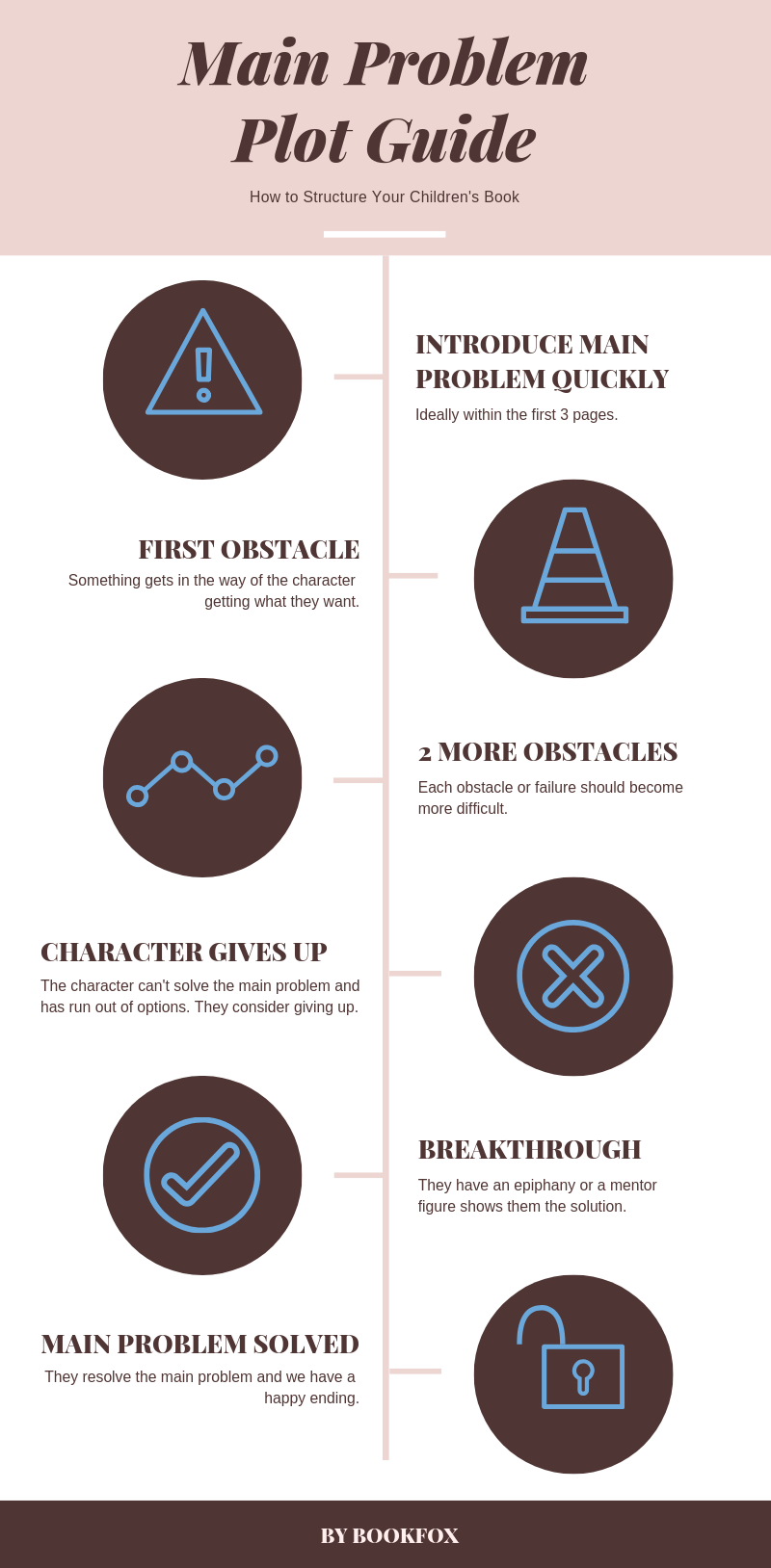

5. Figure Out the Main Problem

Every character has a problem. It could be a mystery, it could be a person, it could be a crisis of confidence. That problem is what they will struggle with for the entire book.

The majority of the book will be obstacles the main character has to hurdle before they can solve their problem.

Here are the main mistakes beginning writers make with their character's Main Problem:

- The character solves the problem too easily. Make your character really struggle and fail. Ideally, the main character should fail at least three times before solving this problem, and perhaps fail as many times as five (if you're writing for older children).

- There are not a series of obstacles. On the character's way to solving the problem, the main character should run up against a whole bunch of obstacles. Don't have him defeat a single obstacle and then voila, problem is solved. To build a rocket ship to fly to space, the main character should lose some parts, his mother should call him for dinner, his friend should tell him it won't work, it should rain, etc.

- The character doesn't care enough about solving the problem. This has to be a HUGE problem for the child — they have to feel like it's a matter of life and death, even if the actual problem is only a missing button. As long as the child feels like it's a huge problem, the reader will feel like it's a huge problem.

6. Use Repetition

Children love repetition! Parents love repetition! Publishers love repetition!

Children love repetition! Parents love repetition! Publishers love repetition!

Everybody loves repetition! (check out my post on 17 fantastic examples of repetition in literature).

If you're not repeating something in your children's book, it's not going to be a great children's book.

I mean, all of Dr. Seuss is basically built on repetition (and he's pretty much the godfather of children's books).

Here are three types of repetition that you can use:

- Repetition of a word or phrase on a page

- Repetition of a word or phrase across the entire book

- Repetition of the story structure

Any book that rhymes is using repetition of similar words, and I would argue that story structure repetition is even more important than language repetition.

7. Write for Illustrators

One of the main jobs of the writer is to set up the illustrator for success. (and you can hire an illustrator from the SCBWI illustrator gallery)

But so many writers aren't thinking about what kind of material they're giving to the illustrator.

If you have a book that takes place inside a house between two characters, the illustrator is going to struggle to draw visually interesting images.

A good illustrator can radically improve your book, but they're also working with what you give them. So give them more:

- Choose fun buildings for your setting (put it in a greenhouse rather than a school)

- Think of funny-looking main characters (a lemur is much more fun to draw than a dog)

- Get out in the open rather than being inside (wheat fields are more entertaining than a bedroom).

Cityscape by Lane Smith

Remember, a publisher isn't only evaluating your book on the words alone. They're thinking about the combination between your words and an illustrator's pictures. And if you don't provide a solid half with the words, they're going to say no.

And if you're self-publishing, good visuals are much more fun for the child!

8. End the Story Quickly

Once the main problem of the story is resolved (the cat is found, the bully says he's sorry, the two girls become friends again), you only have a page or two to finish the book.

Once the main problem of the story is resolved (the cat is found, the bully says he's sorry, the two girls become friends again), you only have a page or two to finish the book.

Since the story is done, there's no longer any tension for the reader, which means they don't have an incentive to keep reading. So do them a favor and end the book as quickly as possible.

Basically, you want to provide a satisfying conclusion and wrap up all the storylines.

One of my favorite tricks for an ending is a technique that stand-up comedians call a "Call Back." This is when they reference a joke from earlier in their set to finish out their routine.

You can use this in children's books by referencing something in the first 5 or 6 pages of the book. For instance, if the main character was so focused on a purple lollipop that they wandered away and got lost, then after she was found the final page of the book might say: "and from then on she only licked red lollipops!"

9. Choose Your Title

Now you may say: why are we figuring out the title after we do all the writing? Good question.

Now you may say: why are we figuring out the title after we do all the writing? Good question.

The truth is that many writers don't know the essence of their story until after they write the book. So you can have a temporary title, but just know that you'll probably revise it after you finish.

And revising is fine! Everybody revises. Don't be afraid to change your title multiple times until you hit the exact right one.

Also, the title is the number one marketing tool of your book. Most readers decide whether or not to pick up your book from the title alone. That means choosing a title might be the most important thing you do (although it's probably a tie with choosing an illustrator).

- Use Similar First Letters (Alliteration). Say your book is about Amy's adventure finding a whole meadow full of poppies, and how she befriended a mouse there.

- Don't Title: "Amy's Adventure with Poppies."

- Do Title: "The Mouse in the Meadow."

- Don't Use a Descriptive Title. Many people just describe the contents of their book in the title, but I would warn against this. For instance, there's a book about a boy who is searching through a vast library to find a special book about eternal life. What would you title this book?

- Don't: "The Vast Library." (Boring)

- Don't: "The Library Hunt." (This is better. "Hunt" is a good word, and the combo with library is intriguing.)

- Do: "How to Live Forever." (This is the actual title, and it's great. This is the name of the book the boy is searching for, and it lets the reader know there will be some deep topics discussed.)

- Use an Action Title. You want energy in your title. A lackluster title will spoil your book's chances for sure. That means you want fun active verbs inside your title rather than passive ones.

- Don't: "Johnny's Wonderful Day."

- Do: "Captain Johnny Defeats Dr. Doom." (Captain Johnny makes it more playful, we have the active verb of "defeat" and Dr. Doom uses alliteration.)

- Use the Technique of Mystery. Does your title tell the reader everything they want to know about the topic or does it provoke their curiosity? Your goal is to give enough information that the parent says, "Huh, that sounds fun."

- Don't: "The Bird in the Window."

- Do: "Oh, the Places You'll Go!" (What places?)

- Do: "Olivia Saves the Circus." (How? We want to know.)

- Do: "How to Catch an Elephant." (Tell me more!)

- Google "Children's Book [Your Title]".You want to see if the title is already taken (or if there is a title that is too close). Now say your perfect title is already used. Can you still use that title? Well, yes. People can't copyright titles. But you'll have a hard time distinguishing your book from that book, so it's not always the best idea.

- Test Your Title with Children and Adults. It's important to see how children react to your title. Are they excited? Do they seem bored? But remember that children aren't the ones buying books — parents are. So make sure to bounce it off some adults as well and get their reaction.

10. A Revision Strategy: Walk the Plank

Most unpublished picture books are far too wordy.

In fact, if you talk to publishers and agents, they will say that children's books being too long is one of the main things that makes them reject a book.

Here is a revision technique that will fix that problem. Make every single word, every single phrase, every single sentence "Walk the Plank."

In other words, you highlight it and hover over the delete button (this is the "walking the plank" moment) and ask yourself: if I cut this, will the story no longer make sense?

If the story will still make sense, then PUSH that phrase/sentence off the plank and delete it.

If the story will not make sense, then that word or phrase or sentence gets a reprieve (at least in this round of editing!).

In general, the shorter your children's book, the better chance that publishers/agents will like it and the better chance you'll have of pleasing children and parents (not to mention shorter books are cheaper to illustrate — and illustration is expensive!).

11. How to Find an Editor

Once you've written your book, you really need to get an expert's opinion to help you improve it. An editor will be the best investment in your book. After all, I know you love what you've written, but there are so many tricks and techniques to writing that can improve the experience of the reader.

Once you've written your book, you really need to get an expert's opinion to help you improve it. An editor will be the best investment in your book. After all, I know you love what you've written, but there are so many tricks and techniques to writing that can improve the experience of the reader.

There are two different types of children's book editors.

- First, there are developmental editors (also called content editors). These editors help you improve the story concept, the plot, the characters, the pacing, the dialogue, and whatever else needs to be improved. They look at the big picture and help you revise your book (this is what I do!).

- After you use a developmental editor, then you would need a copy editor. This is the editor who fixes all the formatting, grammar, spelling, verb tenses, style, and all the other small details. They make your book look professional.

Sometimes you'll find an editor who can do both, but you can't do both at the same time — you have to make all the big picture revisions before you start tinkering with all the small details.

Here is a handy checklist when looking for an editor.

- Your editor should be someone who has been in the industry for a while.

- Your editor should have examples of published children's books that they've edited.

- Your editor should have testimonials from satisfied writers.

- Your editor should be a member of SCBWI (Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators).

The cost of editors vary widely, but if you're not paying at least $300 – $500, you're probably getting someone without a lot of experience in the industry. And you don't want a beginner messing around with your book.

If you'd like to hire me as an editor, check out my children's book editing page.

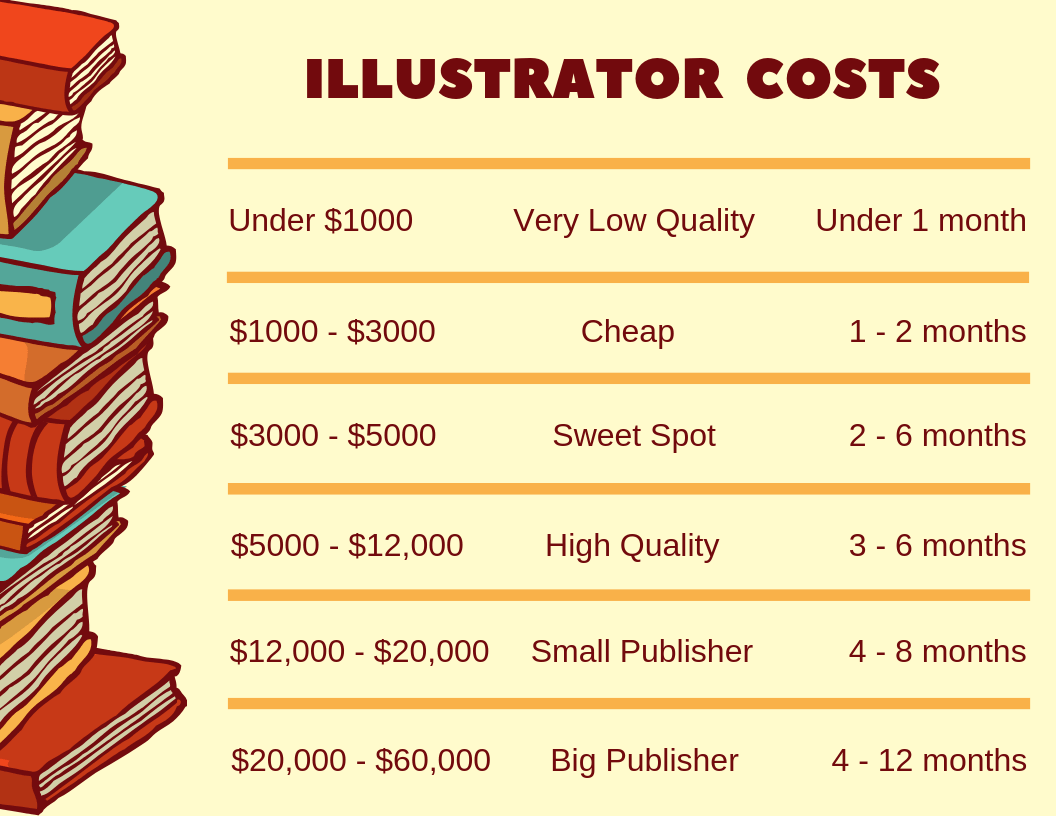

12. How to Find an Illustrator

This is the most important step of the post-writing process.

An illustrator will be the most expensive step of publishing a children's book, but also the most essential for a successful book. The more you spend on this step, the better your book will look. I mentioned the SCBWI illustrator gallery above, but I also wanted to recommend Fiverr as an inexpensive place to hire an illustrator.

If neither of those work out, check out the website Children's Illustrator's or for another option, Illustration X.

When you're considering an illustrator, this is what you should ask for:

- To see examples of previous work (do you like their style?)

- To see a copy of the contract (do they keep the rights or do you?)

- How long it will take (look at the graphic below for average times)

- Whether they also do layout, type, and book design (otherwise you need to hire a book designer afterwards)

Make sure you're really in love with the illustrator's style, and that it matches your vision for what you want the book to look like.

WHAT FOLLOWS IS VERY IMPORTANT.

You can't just throw words up on an illustration and expect them to look good. It's essential to have a happy marriage between text and image. You want to think about:

- The font. This is incredibly important. I see a lot of self-published children's books that selected the wrong font, and it's glaringly obvious. You need an illustrator to help you choose exactly the right font to match the illustrations.

- The size of the font. This is important as well. It should be consistent across the whole book and should pair well with the size of objects in the illustration.

- The placement of the words. If you put the words in the wrong place on the image, you basically ruin the entire illustration. It needs to be carefully balanced and follow good composition guidelines like the rule of thirds. Ideally, the words should enhance the illustration rather than detract from it.

- Page breaks. What words should go on which pages? This is something you need to discuss with your illustrator before they begin. They need to have a say in this — don't just tell them how you want the pages to be broken up. For instance, they might have the idea to have a two-page spread without any words at all, or to separate a single sentence across several pages, or to have one page with a few sentences on it and the next page with just a short phrase for emphasis. This is the number one mistake I see beginning writers/illustrators make: they have the same amount of text on every single page (usually a single sentence).

So either hire the illustrator to do book design, or hire a book designer. But just don't choose the fonts and placements and font size on your own — get a book designer to help you.

Common Questions From Writers

Q: Should I copyright my book?

There are differing opinions on this, but in general I would say NO. You don't have to worry about someone stealing your book. If you go the traditional publishing route, the publisher will copyright it for you. If you go the self-publishing route, you already own the material the instant you wrote it, so getting copyright only gives you added protection.

There are differing opinions on this, but in general I would say NO. You don't have to worry about someone stealing your book. If you go the traditional publishing route, the publisher will copyright it for you. If you go the self-publishing route, you already own the material the instant you wrote it, so getting copyright only gives you added protection.

Now if you're going to chew your nails down to the nub worrying about this, then set your mind at ease. If you live in America, go to the U.S. Copyright Office website and you can register for under a hundred bucks. I walk you through the steps on how to do this in my children's book course.

Q: Do I need illustrations before sending my book to editors, publishers, and agents?

This is a hard and fast NO. Editors want to work with the language alone, so unless your book requires the illustrations to make sense, you don't want to send the illustrations. Even then, you can easily put the illustration explanation in brackets [like so].

This is a hard and fast NO. Editors want to work with the language alone, so unless your book requires the illustrations to make sense, you don't want to send the illustrations. Even then, you can easily put the illustration explanation in brackets [like so].

Publishers always always always hire their own illustrators, so save yourself the money and submit the text alone. This is because choosing an illustrator is a marketing decision (that they need to make, not you) and because a good illustrator can cost $20,000. You probably don't have that kind of money lying around.

Now what if you're the illustrator? Well, then you DO want to send the illustrations. But if you get a rejection, it could either be because of the story or because of your illustrations, and sometimes you won't know what the weak link is.

In general, though, agents are looking to represent illustrator/writers much more often than they're looking to represent writers alone. That's because children's book illustrators earn A LOT more money than children's book writers (sorry, that's just the way it is).

Q: Should I ask for a non-disclosure agreement? (NDA)

If you want to you can, but you have a better chance of a bear eating you than someone stealing your book.

If you want to you can, but you have a better chance of a bear eating you than someone stealing your book.

Plus, if they steal it, you can easily sue them and take all the profits and more, so there isn't much motivation for someone to steal your book.

The truth is that writers worry about this far more often than it actually happens. My advice would be to put all your energy toward creating the best children's book you can create, and if you have a great book, the agent/publisher/editor will want to work with you, not steal from you.

Q: Will you be my literary agent?

No, I'm an editor, and the role of an editor and literary agent are very different. An editor's job is to help you make your children's book the best it can be. The role of a literary agent is to play matchmaker and find a publisher who wants your book.

However, if you sign up for my children's book email list (via a pop-up on this page) I will send you a list of children's book agents. Also, here's another list of agents.

Q: Will you help me find a publisher?

That's mainly the role of a literary agent, but I do have a list on Bookfox of 30 publishers who will accept submissions without a literary agent.

And if you hire me for editing, sometimes I'll be able to recommend a few publishers where your book might be a fit, but it's not like a handshake deal. Publishers get a large number of submissions and they have to take on the books they know they can sell.

Q: How many submissions will an agent or publisher get in a year?

A beginning agent might get 2,000 – 3,000 submissions in a year, while an established agent might receive 3,000 – 8,000 submissions.

A beginning agent might get 2,000 – 3,000 submissions in a year, while an established agent might receive 3,000 – 8,000 submissions.

Publishers who accept submissions get anywhere from between 2,000 submissions to 15,000 submissions, although almost all publishers who start getting too many submissions stop accepting submissions (because it costs too much to hire people to wade through all those submissions).

I don't mean to discourage you, but just help you make an informed decision about whether you should self-publish or seek a traditional publisher. It's really tough to land an agent or a publisher, and it can take a lot of time and work.

What's wonderful about self-publishing is that within a week you can be holding your book in your hands.

Q: Should I self publish or seek a traditional publisher?

So for self-publishing, there's lots of upsides: there's no wait time, and you get complete control of the project (such as cover art and illustration), and there's not that much of a cost if you do it all yourself.

So for self-publishing, there's lots of upsides: there's no wait time, and you get complete control of the project (such as cover art and illustration), and there's not that much of a cost if you do it all yourself.

But … you have to do all the marketing yourself, and you don't have anyone to guide you through the process, and you don't have the reputation of being published by a traditional publisher. You should do self-publishing if you're a real go-getter and you think you can get the word out there about your book.

For traditional publishing, there are also many upsides: you would get an advance (money is nice!), they would handle all the proofreading, ISBN, illustrations, cover art, etc, and they would give you some guidance with how to do the marketing and promotion.

But … it can be very, very hard to get an acceptance from an agent or from a publisher. Sometimes you have to send the story out for a year or two, submitting to a hundred outlets or more. Go this route if you have a lot of patience and you want the book to reach a wider audience.

*

Did you want more advice on how to write a children's book? Subscribe to my email list

So let's review the 12 main points:

- Find Your Best Idea

- Develop Your Main Character

- Write the Right Length

- Start the Story Quickly

- Figure out the Main Problem

- Use Repetition

- Write for Illustrations

- End the Story Quickly

- Choose Your Title

- A Revision Strategy: Walk the Plank

- How to Find an Editor

- How to Find an Illustrator

Please leave a comment below if this material was helpful and if you have any other questions.

Also, please check out my:

- Children's book course — "Two Weeks To Your Best Children's Book"

- Children's book editing — let me help you with your book.

Write Better Books.

Receive a free copy of "DEFEAT WRITER'S BLOCK"

when you subscribe to my weekly newsletter.

Success! Now check your email for your free PDF, "Defeat Writer's Block."

How To Get Started Writing Children's Books

Source: https://thejohnfox.com/2019/02/how-to-write-a-childrens-book/

Posted by: marshallbelank.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Get Started Writing Children's Books"

Post a Comment